Trouble at t’mill

If you have read the page about the origins of le Moulin de la Roche, you’ll know how excited I was to find that our mill was mentioned as one of the properties included in the donation Guy I de Laval made of his lands in Auvers in the original foundation of the prieuré d’Auvers around 1020.

You might have thought that that would be settled for the foreseeable future but intriguingly the mill kept popping up in a number of legal battles over the next few hundred years.

Not a lot was heard about the prieuré of Auvers for about a century after its foundation but in around 1190 the first known prieur was mentioned – Geoffroy de Sonnais. He enthusiastically set about laying claim to all the dues and taxes that the prieuré should be getting, as he felt many had been usurped by local seigneurs, land owners. He started by getting the current seigneur of Laval, Guy V, to restate all the assets that his ancestor had bestowed upon the prieuré at the time of its foundation then set about contesting all the missing rights.

One particularly contentious case was that of Brun d’Auvers, Chevalier and Seigneur of Souligné-sous- Champagne. Brun was the brother of Robert d’Auvers who was Seigneur of Plessis on the outskirts of the village and the two of them had a lot of power and influence in the area. Brun owned half of le Moulin de la Roche, the prieuré having been given the other half as part of its foundation.

The prieur, Geoffroye de Sonnais had had another water mill built on the path to his lake near the centre of Auvers for the villagers to use; le Moulin de l’Etang. Brun d’Auvers felt this was unfair competition and had his son, Gervais, burn down le Moulin de l’Etang. Geoffroy de Sonnais charged Brun and Gervais with the crime of setting fire to church property and the case went before the Bishop of Le Mans. After many hearings ( Geoffroy was already fighting Brun in the courts over Brun’s insistence that he should be able to deliver justice, and receive the taxes and fines from the outcomes in Auvers) Bishop Hamelin set up a commission of enquiry of worthy church archdeacons who were tasked with looking into the matter and coming up with a solution. Hamelin then delivered his sentence.

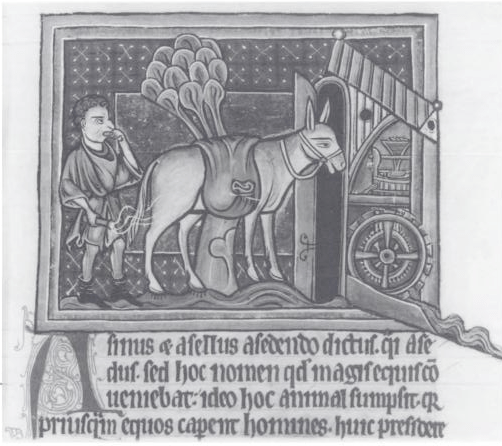

Brun d’Auvers was to surrender one fifth of le Moulin de la Roche to the prieuré and in return he would receive one fifth of le Moulin de l’Etang (which was presumably not worth much as he had just burnt it down!). The flour due to each mill owner, after the millers’ shares had been deducted, would be locked in a chest with two keys and divided into two equal halves. Everyone would be free to choose which mill they used. (Normally, under the seigneurial right of banalité the mill owner had the right to force all the inhabitants of his lands to use his mill, his oven, his wine press – and pay a tax to do so).

In 1235 Robert de Breuil, heir to Gervais d’Auvers’ estate, sold half of le Moulin de la Roche and a fifth of le Moulin de l‘Etang to the Abbey of Bellebranche, a Cistercian abbey about 5km from le Moulin de la Roche.

In 1246 a charter signed by Maurice de Craon, Seigneur of Sablé and Sénéchal of Anjou, confirmed a transaction between the monks of Bellebranche and Robert d’Auvers regarding le Moulin de la Roche-sur-Erve (Rocha super Arvam in latin) in Auvers, which Roberto de Brolio, Robert de Breuil, had given to the abbey and which Robert d’Auvers now wanted back.

The monks agreed to cede their rights to the mill if Robert d’Auvers agreed to give them six and a half livres tournois, per year in cens, property duty.

The Hundred Years war – a series of conflicts in Western Europe from 1337 to 1453, waged between the House of Plantagenet, rulers of the Kingdom of England, and the House of Valois over the right to rule the Kingdom of France, saw repeated destruction of towns, villages and property in France and this area of Maine and Anjou was particularly badly affected, so it’s not surprising that there aren’t a lot of records which survived from this period but the next we hear of le Moulin de la Roche is in a charter from 1446.

During the wars that ravaged the Maine during the time of Charles the VII, the Moulin de la Roche was ruined and the monks of Bellebranche Abbey, who had since reacquired it and who also owned the mills of les Bas Ecurets and la Vieille Panne further down the river Erve, were in no hurry to repair it. They even removed the wheel and the millstones.

The then prieur of Auvers, Gérard de Lorière, who by the agreement of 1190 had the right to a fifth part of the mill and la dîme sur la mouture, flour tax, wanted to force the monks to restore the mill to working order. When the monks refused he lost no time in seizing the revenues of the fief of Haut-Ecuré, which at 200 livres tournois he estimated was the damages/loss of revenue he had incurred over the 25 years that le Moulin de la Roche had been out of action.

This action forced the monks to enter into talks and an agreement was signed on 10th September 1446, between Gérard de Lorière, abbé at la Couture and prieur of Auvers and abbé Etienne of Bellebranche, the terms of which stated that the Abbaye de Bellebranche would hand over complete and entire possession of le Moulin de la Roche ‘cum portino, insulis, chausseis, esclusis, tam in portino quam in insulis et aliis quibuscumque, necnon habitacione in qua morabatur multor ipsius molendini’ (with its islands, roads, lock and miller’s house) for the once-only payment by the prieur of Auvers of unum den. tur. census, one penny of property tax.

Le Moulin de la Roche therefore again came into the sole possession of the prieur and he quickly had it rebuilt using the materials from le Moulin de l’Etang, which was demolished once and for all.

It would appear that the place we now call home has had quite a chequered past! As the current building probably only dates back to the early 1800’s, the mill has no doubt been destroyed and rebuilt more than once. I can’t wait to find out more about the role it has played in local history over the centuries.

Wow! What a history! Then, thinking of the villagers who needed to have their grain ground into flour, how difficult and uncertain it must have been to get it done with armies and fires and angry seigneurs fighting about every mill around.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, Ruth. It’s so quiet and tranquil here today, in the spring sunshine with the birds singing that it is really difficult to imagine that anything terrible or exciting ever happened here!

LikeLike